I recently had the opportunity to speak with the IESE Alumni Association chapter in Dubai and their guests about the link between business strategy and geo-politics. I received a very warm reception from former students and other alumni as well as amazing insights into the current situation in the city and the United Arab Emirates.

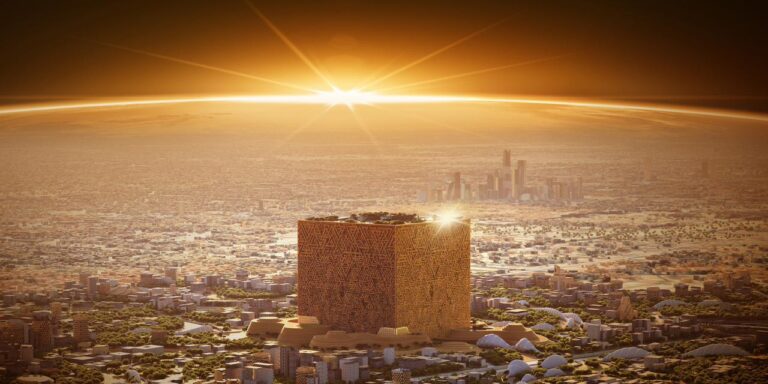

Dubai is a truly remarkable place and they put me up next door to the Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world. The tower is 890 meters tall and has 160 floors. In many ways the building is a metaphor for Dubai and the UAE.

In the first place the tower rises up out of the city and makes everything around it look small even though many of the buildings in the city are impressive in their own right. For me, this aspect of the tower resonates with the rise of Dubai which has risen above its humble origins and now towers over other cities in the region.

Another aspect of the Burj Khalifa is the incredible opulence and wealth that is implied in its construction and the elegance of its structure. In this regard, I see the tower as a symbol of the wealth the UAE has achieved in such a short time.

Between the collapse of the pearling business in the 1950s and the oil boom in the early 1970s, the UAE went through what were called the ‘hungry years’. The UAE has made astonishing progress in the last 60 years. In 1960, for example, the life expectancy, in what were called the Trucial States, was 55 years and GDP per capita was $1,770. To put these numbers in perspective these figures are worse than the current indicators for Afghanistan and Zimbabwe. Today the UAE has, at over $68.000, one of highest GDP per capita numbers in the world and a life expectancy of almost 77 years.

An additional element of the tower that resonates with Dubai is the highly diversified nature of the property itself. Under the motto live, work, play, the tower has residential space, offices, a hotel, spas and gyms for men and women and prime shopping. The city is similarly diversified and has become a tourist destination in its own right.

The Burj Khalifa name also underlies the special status of Dubai. Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan is the Emir of Dubai’s neighbour Abu Dhabi and the President of the UAE. By naming the tallest building in honour of the Sheikh, Dubai’s own Sheikh, Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, sent a very clear message that Dubai understands its role in the UAE and underlined the effective partnership between the two men.

The UAE itself was formed by a similar alliance between the fathers of the two Sheikhs in 1971 and I was told by our alumni in Dubai that the two sons work very closely together as evidenced by Abu Dhabi’s support of Dubai after the financial crisis in 2009. The last point I want to make about the Burj Khalifa is that it also shows how much Dubai and the UAE depend on peace and security in the region.

The distance between Dubai and Iran is just about 160 km across the water that separates them. Like New York’s Twin Towers, the Burj Khalifa stands out as a target in a potentially dangerous part of the world.

I was politely told by by Dubai hosts that the water’s proper name (which I refer to as the ‘Persian’ Gulf in my book, Strategy and Geo-politics) is the ‘Arabian’ Gulf. Names are important to people and it seems that Google has decided to hedge its bets and refers to the water by different names depending on where one is when doing the search. Writing this blog at the airport in Dubai, Google calls it the ‘Arabian’ Gulf![]()

Mike Rosenberg is Associate Professor of Strategic Management at IESE Business School where he teaches in the MBA and executive education programs on strategy, sustainability, globalization, and geo-politics.